Notes from Phnom Penh, Cambodia

These notes started in 1995 as a series of messages from me to what was then a fairly short list of family and friends, mostly in the United States. Most of the messages were sent under the title "Notes from Phnom Penh", so I have kept that name here.

These notes started in 1995 as a series of messages from me to what was then a fairly short list of family and friends, mostly in the United States. Most of the messages were sent under the title "Notes from Phnom Penh", so I have kept that name here.

By the way, if you see anything that is silly, misguided or outright wrong, you can assume I have seen the error of my ways by now.

You can read these notes through top to bottom, or skip around these topics (not all are listed):

First Impression of Phnom Penh (July 19, 1995)

Settling In and fixing some coffee

Just Like Home, in which I notice similarities with Philadelphia

My House, in which I live

A Day in the Life, in which I also live, and take Language Lessons too

Justice: The Gavin Scott case

Misconduct by Men in Uniform

The Conviction of Scott, and the Ransacking of a Newspaper bode ill (November 15, 1995)

Logging Concessions

Cambodian Politics and the arrest of Prince Sirivudh

Hard Words from the Second Prime Minister (December 8, 1995)

Hun Sen Lashes Out (complete text of December 9 speech)

Health Care in Cambodia

The famous Mad Cow incident (April 1996)

The Death of Pol Pot

A Day at the Daily, or how we put out the paper (also see my FAQ on working at the Daily

Easter Sunday: Unusual rituals mark a day of tragedy (March 30, 1997)

Tension rises in the capital, explosions cause panic

Firefight on Norodom Boulevard (July 18, 1997)

Hun Sen Makes His Move: Funcinpec forces are routed (July 6, 1997)

Peace, or Post-Coup Depression? A look back at the damage and conditions in Phnom Penh

How I went from Beach Bum? No! Corporate Executive? Yes!--but not for long

Leaving Cambodia

(See also notes from the return to Cambodia, which picks up in 1998.)

First Impression: July 19, 1995

Phnom Penh is a dazzling explosion of activity in the streets. Hordes

of motorbikes, bicycles, cyclos (three-wheeled pedicabs), and NGO Land Rovers honking.

Motos--carrying monks in saffron robes, or families of five and more--swarm

along potholed streets driving any which way and not stopping for anything.

Broken sidewalks are heaped with garbage. Vendors sell cloudy yellow beverages

in old dirty Coke bottles (luckily before drinking any, I realized it was gasoline). Thousands of kids play a strange game that involves hurling their flip-flops at some

stationary object. The sidewalks are taken over by whatever adjoins them;

iron is worked, motos are repaired, barbershops are set up on them. In between

there are holes like wells that drop ten feet to into bubbling sewage, so

watch your step!

Was this the level of commerce in American cities before shopping malls?

It is amazing that in so poor a country there is so much activity. At night,

seen from the balcony of the Foreign Correspondents Club, the moon emerges

orange and shines over the Tonle Sap and the Mekong River. Down below, the

FCC generator hums amid a crowd of cyclo and moto drivers who await us foreign

correspondents and assorted other drunks in hopes of a fare. The yellow

walls crawl with finger-sized geckos looking for bugs to snap up and finding

plenty. OK, it smacks of the colonial, but there is a pool table, and they

screen movies every week.

Settling In: July 25, 1995

One of the first and most important parts of settling in here in Phnom

Penh was to engineer the best possible cup of iced coffee. When every day

is a sticky hundred degrees F, and follows a late night doing layout at

the Daily, iced coffee is a must. A short moto ride down Monivong is the

Russian Market, a maze of tin-roofed mercantilism best imagined as Philly's

Italian Market made narrow, continuing for blocks of twists and turns with

perhaps a thousand booths peddling fruits and vegetables, moto parts, meats,

housewares, stationery, silk and cotton sarongs to be custom-tailored at

any of 40 sewing tables. It's dark and smells sweet from fruit turning in

the heat, smoky from preserved meats hanging and greasy from the motos that

drive through the two-foot aisles. Finally there's a lady who has plastic

bags of fine-ground coffee. "Coffee Lao. This one seven dollars kilo.

This one eight dollars kilo." I look at each, considering. "This

one good. This one very good." I smell each--she's right--and

buy the eight dollar bag.

At home I turn on the gas and boil up some tap water for a few minutes,

imagining giardia beasties run screaming up the side of the pot and plunging

into the fire below, turn off the gas and spoon in my Lao bean for steeping.

A spoonful of sugar in the mug, and a couple of paper towels, and I pour

the coffee through. Just like home, almost. Oops, I am home. My milk has

gone chunky in the bottle. There must have been an especially long power

outage yesterday, and for some reason Sam-ann won't run the generator during

the day. Or maybe that's just the way milk behaves here. So I go for the

Cow Head milk, which stays good, and get the ice, which I have cleverly

prepared with water purified by my handy filter. Iced coffee, with some

red spiky spur-fruit on the side. Mmmm.

Just Like Home: August 1, 1995

I'd like to give you a feel for the layout of Phnom Penh, since I seem

to be a layout guy now. Since most of you live in Philadelphia, dear readers,

I'm going to use that greene country towne as my template. In fact, the

word phnom means hill in Khmer, and Penh was the name of woman who lived

on that hill, perhaps around the time the capital was moved here. So you

have William Penn and live in Penn's Forest, and I have Srey Penh and live

in Penh's Hill.

Now imagine that the Delaware River is the muddy, mile-wide Mekong, with

Phnom Penh sprawling on its west bank. and that Penn's Landing is a marshy

slope along Sisowath Quay where a few poor families bathe. The Old Market

occupies the place where Philly's Market Street would begin--where Philadelphia's

old market filled the center of the street, Phnom Penh's Old Market still

fills a city block. But its real history is just as certainly erased: the

vibrant Chinatown that existed there--very close to where Philadelphia's

Chinatown is on my template--was wiped away by the Khmer Rouge in 1975.

Now it is a Khmer market like the others, fronted by a row of twenty or

so stationery booths selling the identical limited selection of goods. As

you walk west on what would be Market Street you enter the monumental center

of town; that area with the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications, the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the French-subsidized Petit Lycee where my

Khmer classes start on Monday, the major banks from France, Thailand, England,

and Singapore, and Cambodia's own National Bank and Foreign Trade Bank,

where I have opened an account. Off to the side of this center is Wat Phnom,

the "Hill Temple", which with its park-like surrounds and rotary

parallels Philadelphia's Basilica and Logan Circle.

Back inside the Foreign Trade Bank are rows and clusters of clerks maneuvering

around piles of paper files, file cabinets, hanging folders, and bins full

of forms, receipts and ledgers. There are three PCs, and nobody is using

them. Paper money in bales sits on tables in the rear (it has been rumored

that the Foreign Trade Bank keeps all its deposits in cash in the vault).

When I first changed $50 into riel, I was given a half-brick-sized bundle

of pink 500-riel notes, which are the standard unit of currency. One of

them, about 22 cents, will buy two loaves of French bread, one melon, or

half a moto ride. The 10,000 riel note, worth almost $5, is next-to- impossible

to get rid of because most vendors don't have enough change.

The major north-south thoroughfare, Monivong, is our Broad Street. As it

heads south, buzzing with motos in clouds of yellow dust, it passes near

the Russian Market, which I compared earlier to Philadelphia's Italian Market,

and also the Olympic Stadium, a cold gray concrete bowl where I watched

the Chinese soccer team of Shenzen province humble the Royal Air Cambodge

side (despite their splendid new Marlboro uniforms). Above the rim of Olympic

stadium only the tops of two elegant wats are visible. Down at the edge

of the ragged field three sets of honor guards, each carried their fluttering

standards: China, Cambodia, and Marlboro. Prince Ranariddh, the First Prime

Minister and heir to the throne, sat impassively at a small pink- draped

table in the upper stands. He is reputed to be a big fan, so he probably

did not hesitate to cough up the admission: 90 cents for the good seats

under the roof. The total gate was about $2700. Twenty years ago Olympic

stadium hosted what Veterans Stadium never has: hundreds of military officers

and government officials of the defeated Lon Nol government arrived at the

stadium to find out their assignments under the new regime. They were slaughtered

en masse on the playing field.

West of downtown is the University of Phnom Penh's main campus, a collection

of semi-abandoned three- and four-story whitewashed buildings set in an

expanse of dust. Perhaps they spruce it up for Alumni Day as Penn does.

Our journalism workshop is on the second floor of the front-most building,

still awaiting a huge gift from Walter Annenberg.

Beyond the campus is Pochentong Airport with its one strip and brand-new

terminal building. The airport also houses a dozen or so expressionless

customs and visa officials who preside over the fairly quick but mysterious

visa process. Just go where most people are going, and then do what they

do, and you'll get through with a one-month visa. Tomorrow King Sihanouk

will land at Pochentong and I am told that this means there will be a vast

welcoming crowd of semi-worshipful Khmers. Warren Christopher may get the

same on Friday.

My house is off Monivong on Street 334 (bei-rouy samseb-bouen), in what

might pass for a northern section of South Philly or perhaps even Queen

Village. Don't be misled by my street's high number; the next street north

is 322, then 310, even though they are set closer as close as Philadelphia

blocks. What were they planning for those extra numbers? My block passes

for a very typical wealthy block here. Walls and gates face the street,

topped with spikes, razor wire, or broken bottle shards set in mortar. Behind

the gates are small patios. If wealthy people actually live in the house

or if and NGO (non-governmental organization) has set up shop there, there

will be a car and probably a guard or two dozing on straw mats inside. The

corner house has a solid metal gate with two small holes through which two

small dogs poke their heads, bark, and make me think of baseball.

It is equally likely on my block that a house is abandoned and stripped,

or has been split up and lean-tos added for a self-contained slum effect.

These seem more in keeping with the street itself, which has no trace of

pavement, only rutted dirt. Recently some of the biggest holes which daily

filled with rainwater have seen the attention of a kind of limited public-works

project which has filled them with soft, loose dirt in some cases, and others

with broken rubble including concrete chunks as big as your head. There

are a couple of stores on the block: small lean-tos of wooden poles with

corrugated metal roofs which sit on the margin of the street, staffed by

children, selling some mysterious candies, fried something and a few household

goods--again, the selection identical everywhere.

My House: August 17, 1995

pteah = house

Mine is called the Medical Annex, and it's three stories of concrete, starting

with a little paved courtyard where the well is, and the generator for when

city power goes off, which is often. If you go in the iron gate, and cross

through the courtyard you would walk into the house--our ground floor--of

Juron and Toun-sarouen, which is the ground floor of our house. Juron and

Toun-Sarouen are our two guards. Juron lost his left leg to a land mine,

and Toun-Sarouen is crippled by polio; both of them used to repair bicycles

for a project run by the same foundation that runs the Cambodia Daily. Juron

is a Cham, a Cambodian Muslim. Both of them got tired of living alone, so

last week they built their bed-platforms into four-posters, hung up draperies

around them, and invited their wives and kids to live in. Our ground floor

is now a sort of tent encampment in a 12 by 20 foot room.

Also sleeping in the ground floor is Sam-ann, the house manager, a hyperactive

22-year-old student. He unlocks the gate when Roy and I come home at midnight

or 1am from work. Sam-ann gets frequent headaches ever since he fell out

of a coconut tree on his head years ago, so he often has the red streaks

on his arms which come from rubbing them with the edge of coin. Another

popular technique here is to press suction cups or hot glasses on your forehead,

so you see a lot of people with big red circles, and you know they had a

bad day.

Narrow stairs up the side of the house lead to the double wrought iron and

glass doors to a cavernous living room. This must have been the house of

a Lon Nol general in the early seventies. In front is a balcony with potted

palms, a good place to sit when the generator isn't chugging the air full

of smoke, next to an office and bedroom suite that houses Mrs Shimamura,

the Japanese pharmacist, for 10 days each month.

Roy and Tinker live in a dark-paneled room off the living room. Roy is my

fellow layout editor, and Tinker writes freelance. Both are taking a year

off from the Raleigh News-Observer in North Carolina.

This living room really echoes. There's not a soft surface in it; the floor

is tile and the walls are concrete. One wall is filled with an enormous

burnished plaster relief on an Angkorian military theme.

Past the door the room I started off in, a dull dormlike cube, another double

door leads down a short corridor. First is the room of Chaeng, our maid,

who daily makes our beds, washes our clothes, does our dishes. This takes

a bit of getting used to, but I suppose I can. If it were your job to do

the dishes, you wouldn't want someone else to do it, right? Chaing is 32,

and unlike Sam-ann cannot speak any English. So my conversations with her

have been limited to about one word in length. All Westerners seem to live

like upper- middle class Khmers here. Guards and maids seem to come with

the house, and in fact any Westerner is free to walk into almost any house

occupied by other Westerners, as the guards cannot speak English and are

normally unwilling to challenge them.

Then you see our kitchen, not badly outfitted with a small refrigerator,

gas stove and sink. Since the electricity goes off all the time, things

in the fridge tend to melt and refreeze a lot. We have collected five dishes,

four glasses and several pieces of silverware so far. This is where I pump

drinking water through my filter, and draw circles around the tiny ants

with the special chalk they hate.

Next is a long bathroom, also quite well outfitted with an electrical heater

for the shower water--which is quite unnecessary given the usual sweat level.

Outside the bathroom door is a closed metal accordion-type door, through

gaps in which one can watch the activities of the family living behind our

house under a large metal roof. They have a set of shiny red living room

furniture that looks like it was pulled out of a '57 Chevy, and it's said

they are the people to go to if you've lost something and need some magic

done to find it. They also do some palm-reading.

Moving on, a very narrow flying staircase, also made of concrete leads to

my leafy bower...

A Day in the Life: August 30, 1995

Sok.supbaay? (How are doing?)

Knyom sok.supbaay. Choh neak? (I'm fine, you?)

By popular request--or at least one request, anyway...

Episode 5:

After five weeks here, my daily routine is surprisingly regular. More so

than it ever was in Philadelphia, maybe because I have less of everything

and fewer options. Which is not a bad thing so far.

At 9:30 or so the beeping wakes me up for Khmer class. If the electricity

has gone off in the night, it is already very hot in my top-floor room (another

re-creation of my past life in the attic room Philadelphia?). In my bathrobe

I step out of my room onto the roof of the house, which is a red-and-white

checked patio. The sun is beating down with an intensity that surprises

me every morning. I think it is cooler here at night and in the shade than

in a US heat wave, but the direct sunlight here, burning through the thinnest

possible atmosphere, is searing.

My room and the adjacent one are built on the roof of the main house like

a second, little house, with the roof deck forming sort of a yard around

it. Here I have set up a hammock with a blue tarp over it, but it is rare

that I have a chance to use it. A few steps away from my front door is a

bathroom, in its own rooftop structure, which I do not use much because

its water reservoir is very small and provides little pressure. The shower

just dribbles. The other structure in my yard houses the steep concrete

stairs down to the second floor, where I take a shower. I inspect my bath

towel very closely every morning, since the day I discovered--with great

personal discomfort--that it was infested with the tiny red ants that bite.

Every morning Roy, Tinker and I plan to thoroughly review our Khmer over

breakfast, while we listen to Professor Longhair or Hank Williams on my

personal stereo, which is hooked up to $3 speakers, one of which blew out

in the first hour after I bought them. So far our maximum morning review

has been ten minutes, and then we head off to class on our bicycles.

People here tend to ride their bicycles very slowly. Many of the bicycles

are Peewee Herman-style red high-rises made in Thailand with padded back

seats over the rear wheel, and others are stripped-down touring bikes from

decades past--no paint, no chain-guard, bald tires and sagging chains--they

look like ghosts of bikes but are still going. Then a few, like Roy and

I, have cheap Chinese-made mountain bikes which are great on the potholes

but will probably only last a year or so. Our comparatively fast riding

often inspires cheers and whoops from Cambodians, who must think we are

a little nuts. We go up Street 63, which is one way except for the people

going the other way, past the enormous yellow-domed New Market. We are threading

our way through the eddying streams of cyclos, motos with five people on

them, bicycles, motorcycles hauling wagons, white sedans with darkened windows,

cyclos loaded with bricks, scooters piloted by 11-year-olds, truckloads

of soldiers, whatever.

At the Lycee Francais (briefly used as a detention center for the overflow

from the Khmer Rouge's urban liquidation centers) is Setha's Khmer-language

class. Setha is 40 but he looks about 25, an animated instructor who plays

out hilarious mimes. His shy Khmer girl act is a scream. This language itself

is quite remarkable. The only difficult thing about it is the vowels, of

with their are about 60, so many that to write it out in the Roman alphabet

there is a special transliteration system with a whole bunch of mutant vowel

symbols and combinations thereof.

Other than that, Khmer is as logically constructed as could be. There are

no conjugations, or inflections of any kind. No plural forms. No tenses,

other than a word for "will" and a word for "did". And

the more complicated words are all compounded from the shorter ones, like

milk is "water-breast-cow", clothes is "shirt-pants",

university is "universe-knowledge-place". There are lots of great

ones. Money is "looy", because when the French brought it there

were pictures of Louis on the coins--as the story goes. The word for justice

means to work the scales. And the word for "in the near future"

literally means "behind", because since you can only look at the

past, the future must be behind you...follow me?

My classmates, in addition to Roy and Tinker, are an Australian English

teacher, a young Japanese/Indonesian couple on a Christian medical mission,

an older American missionary couple, and a Japanese child care worker. They

are quite reflective of the expat community here, which is made up mostly

of Westerners and Japanese people who work for the foreign media, the UN,

or other non-governmental agencies (NGOs); businessmen from Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia; and various missionaries. These three groups do

not mix together much.

Class ends at noon, leaving me with two or three hours free. This is the

variety portion of my day, during which I might go to one of the street

markets, do errands like shopping for a bicycle on street 182, or eat. Just

a block from the school is the Seven/Seven grocery/restaurant/bar, a good

place to see some BBC news from their satellite dish. It is the most elaborate

of three or four stores selling expat products like spaghetti at extortionate

prices--if you have to have beef that comes from Australia in plastic wrap,

come here and pay $16 a pound. Otherwise, you could buy it from the lady

at the Olympic Stadium market, who according to eyewitnesses sits up on

the table and balances on her posterior as she lifts the slab between her

bare feet, her long, curving toenails digging into its flanks for extra

gripping power while she carves off your piece. I will have to see this

spectacle for myself.

But I admit it, sometimes Roy and I go to the absolutely sumptuous $6 lunch

buffet at the Allson Hotel and sit in air-conditioned splendor, wiping the

street dirt off our faces with white linen napkins and eating two day's

worth of European, Japanese and Khmer dishes. Another good place I've found

is a restaurant by the Boeung Kak lake, an unexpected beauty spot in the

city where they serve a delicious Khmer fresh (uh-oh, that means raw) beef

salad.

Lunch is also a good time for a bike repair by the side of the road. Between

the heavily potholed roads--where there's a surface to have potholes in--and

the cheap tubes, flats are frequent. Springing up to serve the need are

hundreds of sidewalk flat-tire fixers who for 20 cents will pull out your

inner tube, still on the axle, find the hole with a tub of water, and hot

patch it using a vise-like press which is made of a piston and footpeg from

a moto, welded together, filled with burning oil. Nothing much goes to waste.

By around two I am usually in our newsroom on the second floor of what was

previously a massage parlor and brothel. Upstairs we have a whole floor

of tiny rooms partitioned off from each other. Now not in use, of course,

except for staff napping. The job scene I'll leave for another time, but

for now suffice it to say I get out usually between midnight and 1am. Sometimes

a few of us will stop at the Irish Rover-- an actual Irish bar--or the Heart

of Darkness for a post-work beer, but usually it's too late, and I just

pedal home through quiet streets in the nighttime cool, passing by the looming

mass of the Victory Monument, late night noodle stands, red-lit massage

parlors, hopeful moto-drivers looking for fares, and bunches of cyclos,

their drivers asleep in the passenger seat after a hot day of pedaling.

After bumping through the potholes on my street, I ring the bell and Sam-ann,

rubbing his eyes, unlocks the gate, Inside the all is quiet but the raspy

cluck-cluck of the geckos on the walls.

Justice: October 2, 1995

I.

Dr Gavin Scott has been in a cell in Phnom Penh's T3 Prison for three months

now, since before I arrived from the United States. All the acclimating

I have done has taken place while Dr Scott sits in his cell, accused of

rape.

Originally, Dr Scott was accused of sexual intercourse with underage boys,

but now it seems that the charge has been amended, possibly because his

accusers may not be underage at all. It is difficult to tell, because the

specific charges against him have not been made public; nor have the identities

of his accusers, who are backed by several non-governmental organizations,

or NGOs. These NGOs are dedicated to the absolutely noble cause of fighting

"sex tourism" in Asia--one of the many repulsive results of the

gross disparity in wealth between the North and the South, or the East and

the West, or the industrialized nations and the third world, or the old

and the young, or the men and the women, or the rich and the poor.

In Phnom Penh, there are some foreigners who are not NGO staff, journalists,

technical consultants, missionaries, investment analysts, embassy staff,

development specialists, wealthy adventure tourists or hippie backpackers.

These others are the sex tourists, who come to Phnom Penh for reasons that

lurk in the back of your mind (don't they?), but have come to the fore in

theirs. Perhaps Bangkok isn't exotic enough, or too expensive, or too riddled

with AIDS, or too done it already, been there and looking for something

new. Here in Phnom Penh a policeman earns $10 to $20 a month, a government

official $25. So how much of a person can you buy for five dollars, or ten?

But Dr Scott is no sex tourist--or not the usual kind. He was the doctor

at a small local clinic serving mostly western NGO staff. Until recently

he enjoyed a good reputation as a caring young doctor who gave attentive

treatment for reasonable rates, and whose homosexuality was not a matter

for condemnation or even particular attention. Or so I understand, because

I only know of him as a inmate of T3 awaiting trial.

Those who condemn Scott, the certain NGOs, were intimately involved with

the investigation against him and with his arrest. They would like to see

an example made, to show that sexual predation will be brought to account,

that being a doctor, even one with important friends and a social reputation

does make one immune from prosecution. Scott's defenders say that these

NGOs have enlisted the Cambodian organizations which usually defend the

accused, leaving Scott--whose safe was broken into and his small savings

stolen since he was put in prison--without an experienced defender. An English

volunteer lawyer is not permitted to meet with him, as the law specifies

that only Cambodian lawyers may represent the accused. Scott's defenders

say he is being railroaded by faceless, nameless accusers, backed by organizations

which should instead go after the heterosexual sex tourists who daily commit

crimes against the dignity of young girls. Understand that this is country

where sex slavery is commonplace.

Dr Scott is sitting in his cell right now. He doesn't deny that he is gay,

nor that he has had sex with young men. He does deny that he has committed

rape. Reportedly he has lost a lot of weight in T3, and cries frequently.

What are they going to do with him? Decisions in Cambodian courts are not

often made on the basis of the rule of law and careful consideration of

the evidence. Remember, the judges are only being paid $30 a month. Free

Dr Scott, and Cambodia will be known far and wide as a playground for sexual

exploiters, where authorities turn away from the horror so that one more

natural resource can be sold off like a timber concession or mining rights.

Convict him, and the rule of law, already tattered, will acquire another

hole.

When the government tries Dr Scott next month, it will have been decided

already: While Gavin Scott sits in his cell in T3, less than a mile away

in some ministry building, are men deciding his fate. They are on trial

as much as he, and on the same evidence.

II.

I say the mangiest dog ever the other day. This creature had no fur, just

leathery droopy skin and sores, and sad eyes. It snuffled through a trash

pile for whatever had been left behind by the people who threw it out, the

people who picked through it, the other dogs that got there first. This

was a leper among dogs. But even the mangiest mutt starving in Phnom Penh

wants to live.

III.

Last night I was taking my dinner break down at the Irish Rover, where Jimmy

Kennelly serves up foamy Angkor beer and the finest whiskey along with his

profanity-laced stories of youth in Ireland. As I supped on Irish stew I

watched the big hurling championship on the TV. Offaly was battling Clare

in the Gaelic Game in Dublin, and in Phnom Penh some thirty assorted expats

peered at the TV trying to figure out the rules and pestering the few actual

Irish there to explain it. Suddenly the power went off and I imagined that

referees whistles blew in Ireland. "Hold it lads, the power's down

in Phnom Penh, the folks at the Rover can't see the game....All right, it's

back. Play on!" In effect that's exactly what happened. When the electricity

reluctantly began to flow again, Jimmy started up the VCR and the players,

frozen in time not for two minutes but for two weeks, resumed their graceful

violence right where they had left off. (The magnetized particles representing

Clare went on to victory.)

Spotlight on Misconduct by Men in Uniform: October 10, 1995

Norodom Boulevard, named for the royal family, is one of two north-south

axes of Phnom Penh. From the massive and ungainly Independence Monument

north to Wat Phnom, the pagoda on the hill, Norodom is lined with embassies,

banks, and mansions both occupied and abandoned. It is the showcase street

of Phnom Penh, which is probably why it was recently closed off to motos,

bicycles, and cyclos. So if you have a car, you can drive on Norodom, but

if you don't you will be whistled down by one of the traffic police who

populate each intersection in groups of four or five.

Time was, I'm told, that these unarmed and underpaid officers could be safely

ignored. One acquaintance was riding on the back of a moto-taxi, in mid-conversation

on a mobile phone, when the whistle blew. His driver tried to speed up,

but the frustrated officer grappled with him momentarily. The moto driver

shook him off and accelerated away. My friend looked back to see the officer

picking up his cap from the dusty road, and continued his phone conversation.

It makes me a little heartsick to imagine humiliation like that. I try to

keep that in mind when I am whistled down. Now the traffic cops have been

reinforced by heavily armed military police, and it's considered good form

to pull over. I've seen people pull over fast when they hear a burst of

AK-47 fire over their heads. The only reason anybody ever stops for police

is the fear of getting shot by them, not any legal sanction. After you are

pulled over, it is your opportunity to supplement the meager salaries of

the cops on that corner. The first time I was pulled over, I showed my Pennsylvania

driver's license. Things that look official often work well here, but my

guy wasn't biting.

"Ah, here we drive right, in Americ drive left. License not good."

Really we drive right side in America too.

"Ah, OK, is good then. Ah, this is captain; he want you pay cigarette

fine, one dollar."

Wait, I don't smoke--oh right, cigarettes for him. OK, fine, here you go.

"Thank you. You no license plate." That's a fact.

"You pay me twenty dollars, I get license plate for you. You pay now,

you meet here tonight, OK?"

Eventually I convinced him that I didn't have enough money on me to double

his salary just then, but I would consider it and maybe stop by later. The

next time I got pulled over it was worse. I was on my bicycle and I came

out of a one-way street the wrong way. It cost me two dollars, which I paid

quickly because the MPs were coming over and I didn't want it to go up to

two dollars each. "It wrong way, you must pay fine at office, two o'clock"

What office? "Oh, you busy, you work two o'clock? OK, you can pay me

now."

At least it's not like when they installed the traffic lights a couple of

years ago. Nobody here had seen these things before--and still there are

only two or three intersections with lights in Phnom Penh--and they didn't

pay much attention to them. The traffic police adopted a simple strategy.

When someone ran the light, the officers would block their path, pull them

over, and beat them up on the spot. It worked. Unfortunately the traffic

lights themselves rarely do.

But this is minor corruption, on the street-corner level. Sometimes the

schemes get bigger, as when one of the editors of the Cambodia Daily was

held up at gun point by a uniformed soldier and two accomplices, in front

of his apartment, and relieved of his cash, his mobile phone, and his rented

Honda Rebel 250 motorcycle (far and away the most popular make among tough

guys). Later, he received a call from someone at the Interior Ministry,

offering to sell him his mobile phone back for $50.

Also in the recent news, a couple of officials from the Ministry of Defense

who kidnapped several young women and carted them around the country trying

to get an acceptable price for them at the brothels. Disappointingly, they

were only offered $70 apiece when they had hoped for $250. At least they

were caught--in that one case.

Some of the corruption in the military is individual like that. There's

a fellow named Sath Souen, an army officer in the north, who is getting

quite a reputation. Called to the scene of a suspected burglary, he shot

a 14-year-old. When police arrived and pointed out that the lad was still

alive and needed to be hospitalized, Souen, witnesses say, shot the boy

dead, saying "No need. Feed him to the fish now." He is reputed

to have killed up to 25 people in Kompong Cham province, including a local

reporter who had implicated a general in some corruption scheme. The military

and the police have been squabbling over whose job it is to bring this fellow

in.

But the larger-scale corruption on the part of the military stems from its

use as a private armed force, or more accurately armed forces. Last week

when the government closed down nine unlicensed casinos in Phnom Penh, one

of them soon reopened, with 50 armed soldiers on guard to prevent the police

from closing it down again. One of the two licensed casinos, actually a

large refitted boat in the Mekong, also hires uniformed soldiers as guards.

When the police arrived one night to harass some vendors, the soldiers--presumably

paid for protection by the vendors--intervened. A firefight broke out, right

in front of the ritziest hotel and casino in the city, and two policemen

were captured by the soldiers. One police captain was held and beaten for

two hours. Now the Defense Ministry has offered to pay the police department

$600 to make up for it, but it's not enough for the police captain, who

promises to exact appropriate retribution.

A day or two after that incident, a Malaysian official of the same casino

disappeared. He was kidnapped and held for ransom by--surprise!--army officers

who were supposed to be guarding him. Several days later police stormed

a house in the provinces and rescued him. Thus it was demonstrated that

foreign investors are indeed safe here; I mean, he was rescued!)

These same underpaid, undertrained soldiers and police are on guard outside

the house of the Second Prime Minister, Hun Sen (a former member of the

Khmer Rouge, who escaped an internal purge by fleeing to Vietnam and later

returned as a puppet leader of the Vietnamese-dominated invasion force that

overthrew the KR in 1979.)

So there they are, guarding Hun Sen's house next to Independence Monument

on a certain night last month. The town was buzzing with rumors that troops

loyal to First Prime Minister Prince Norodom Ranariddh were on the move

toward the capital, so maybe the troops guarding Hun Sen's place were nervous

when a motorcycle rode past. They opened fire. The rider, Ian, who works

for Land Rover, knew only that it was dark and someone was shooting at him.

He sped up, but bullets hit his front fork and his leg, and one grazed his

head. When he woke up he was on the ground. The soldiers--in the process

of stealing the motorcycle--were surprised to see him wake up, and scattered.

He managed to pick up the bike and roll it to the nearby Irish Rover, stepped

in and collapsed. While he had been unconscious his wallet and telephone

had been stolen, but he escaped with minor injuries. Moments after Ian was

shot, the same soldiers peppered another motorcycle with bullets and brought

down two Bulgarians--one the son of an embassy official--and a Brit.

All are now recuperating, but this incident did nothing to help Cambodia's

Ministry of Tourism in their efforts at damage control after the travel

guide "The World's Most Dangerous Places" listed Cambodia in the

top five ("Hell in a Handbasket" is the name of the chapter).

They invited the author of the Cambodia chapter to come back and see how

safe it is. So he arrived and only days later foreigners were being shot

at by trigger-happy soldiers in front of a prime minister's house.

Also in the recent news:

The government has removed signs warning of the risk of AIDS in the brothel

neighborhood of Tuol Kork, because the signs were sexually suggestive and

projected a negative image. A crackdown on brothels in general supposedly

continues.

The governor of Svay Rieng province was pulled over by police who fired

at his car and shot at him as he fled. He hid behind a villager at the side

of the road, insisting that he was the provincial governor, until luckily

for him a locally known official arrived and vouched for him. The governor

angrily denounced police procedure, saying that when he was a police officer

himself, he knew that you should make sure you have the right person before

shooting them.

A rocket grenade damaged the house of Nuon Nguon, the editor of a morning

newspaper. This editor has been in a running feud with the editor of another

Khmer paper named "Island of Peace", which has run pictures of

Nuon comparing him to a monkey and wondering how such a hard face might

be softened. Maybe they found a way.

An Internet hoax is in the news here. Apparently a Reuters story was altered

and posted on the net somewhere (maybe on soc.culture.cambodia?), quoting

King Sihanouk as saying that Cambodia should cede some provinces to historic

competitor Vietnam, in order to thank them for invading and overthrowing

the Khmer Rouge. After strong denials from Sihanouk that he ever said this,

the above-mentioned newspaper recommended that people should go the home

of whoever perpetrated the hoax and split their monkey face with axes. That's

thoughtful commentary for you.

And in other grenade news, someone or someones tossed a couple of them into

a party congress of the third-largest party, the Buddhist Liberal Democratic

Party, which is in the midst of a bitter split. No dead, but a lot of dangerous

speculation about the guilty parties. Well, I'm sure a confession will be

beaten out of somebody.

Gotta go--the Cambodia National Basketball Team is playing an exhibition

game at Olympic Stadium versus the Ragtag Expats, who include a few friends

of mine. The REs hope to not to lose by more than a two-to-one margin.

Telephones in Cambodia: 10,000 land lines, 10,000 mobile

Parking garages in PP: 0, 1 on the way

Broken sewer pipes in Phnom Penh: 30-40%

Hours of electricity per day: 10-22, depending where

Potable water: available over the counter

Valium, Xanax, more: available over the counter

Prostitutes testing HIV+: 36% (listen to NPR report, Nov 1996)

Limbless "toddlers" who do tricks to earn money: 2 that I've seen

News and comment: November 15, 1995

(written by me except where noted)

Gavin Scott Convicted, Will Serve One More Month

Dr. Gavin Scott, of whom I wrote in #6, was tried on the same day the solar eclipse passed over Angkor. He was convicted of rape, although it is unclear

whether he was convicted of actual rape or or attempted rape, both of which

are covered by the same law. "Everybody knows those boys are prostitutes,"

an angry Scott reportedly said as he was led back to T3 prison. "They're

lying." Scott will serve one more month for a total of five months.

The rest of his two-year sentence was suspended. Scott has not said whether

he will remain in Cambodia.

S'porean Killed Testing 'Magic Power'

By James Kanter and Chheang Sopheng, The Cambodia Daily

A 22-year-old Singaporean disc jockey was shot dead Friday afternoon

about 30 kilometers north of Phnom Penh in what police are calling an accident

involving a talisman's allegedly magical powers.

Chiang Hock Goan, who was popularly known as DJ Suave, was shot once in

the stomach...after he asked a soldier to fire a pistol at the good luck

charm to test its powers...[it turns out the soldier may be a Khmer Rouge

defector, as well]

"At first, the Singaporean man put the object on a gate and asked the

soldier to shoot at it," said Mau Chandara, noting that the object

was of "Muslim" origin and about two centimeters in height.

"The soldier pulled the trigger three times at the object but there

was no reaction from the gun. Afterwards the Singaporean put on the object

as a necklace and then asked the soldier to pull the trigger again. Unfortunately,

that last bullet fired and went through his stomach," Mau Chandara

explained.

Sources at FM 99, where has Chiang had co-hosted the "Lunch Hour Hot

Hits" program since June, said the DJ had been increasingly interested

in the supernatural.

"At least in the Khmer tradition, you must not test these objects for

their power. If you believe you just wear them," said Station Manager

Som Chhaya.

Newspaper Office Invaded and Ransacked

The New Liberty News, a Khmer-language paper in Phnom Penh, was invaded

by three truckloads of angry villagers who beat a staff member and destroyed

the computers and office equipment inside. The newspaper had been critical

of development efforts in the village of Krainyang. Second Prime Minister

Hun Sen, the sole sponsor of the development efforts there, later told a

group of the villagers that they had a right to do what they did, and he

would be happy to provide the trucks for further efforts.

Second Forestry Concession Sells off 4% of Cambodia

The Cambodian government has sold logging rights to some 4% of the entire

area of the country to one Malaysian company. A few months ago they sold

a little over 2% to an Indonesian company. The area sold is 18% percent

of Cambodia's forest cover. Have members of the government seen the satellite

photos of Madagascar, where the surrounding ocean is stained blood-red as

eroded soil flows from every river outlet after similar levels of deforestation?

It seems that Cambodia as a nation is forced by its poverty to prostitute

itself on the world's streetcorner, even as it collects dwindling welfare

checks in the form of international aid, which is being replaced by workfare

in the form of loans that are offered on condition that the economy privatize.

Privatize how? See above.

Big Fish: November 21, 1995

In the vastness of the United States, political change is felt like swells

rising and falling slowly in the ocean. They are caused by complex forces,

by undersea rumblings and swirling weather patterns. No individual can drive

these changes; the heaving surface lifts some, and swamps others.

Cambodia is a small pond, but this past week the waves have been crashing

in its dark waters. On Friday evening, tanks surrounded the house of Second

Prime Minister Hun Sen, as soldiers, on his orders, placed Prince Norodom

Sirivudh under house arrest a few blocks away on Street 240. King Norodom

Sihanouk, the half-brother of Sirivudh, and Sihanouk's son Prince Norodom

Ranariddh, who is First Prime Minister, were unable or unwilling to stop

it.

Sirivudh is the one who played the American classic song "Feelings"

on his electric guitar at the King's birthday breakfast on October 31 (see

above). Now he is accused of plotting the assassination of Hun Sen, who

applauded along with the rest, but perhaps was not truly moved by the performance.

The allegation is based on a newspaper report, denied by Sirivudh, and a

snippet of audio tape from an unknown source.

There are two large parties in the current coalition government, and one

small one. The party which won the UN-sponsored elections by a narrow margin

is Funcinpec, the "formerly royalist" party which Ranariddh represents

as First Prime Minister, and of which the now-imprisoned Sirivudh is general

secretary. Internally, Funcinpec is in some disarray. Assembly member and

minister of finance Sam Rainsy was first kicked out of Funcinpec for protesting

corruption and was then kicked out of government altogether. His newly formed

Khmer Nation Party was declared illegal last week.

The other major party is the Cambodian People's Party (CPP), which is the

direct descendant of the Vietnamese-sponsored government that was installed

in 1979 after the Khmer Rouge were driven back to the western hills and

forests by the invading Vietnamese. The "formerly communist" CPP

is headed by Second Prime Minister Hun Sen, who was Khmer Rouge himself

until 1978, when he escaped the KR's internal purges by fleeing into Vietnam.

There he joined with Heng Samrin (later to be president of the Vietnamese-installed

regime) and Chea Sim (now the CPP head of the national assembly) as figurehead

leaders of what was purported to be a force of Cambodians liberating their

homeland with the help of a few Vietnamese advisors, but was in fact a full

invasion by the Vietnamese (see Elizabeth Becker's "When The War Was

Over")

The third and much smaller party is the Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party,

founded by Son Sann, who previously had raised his own non-communist army

of resistance to the Vietnamese. The BLDP ruptured earlier this year into

two factions, one headed by Son Sann and the other headed by Ieng Mouly,

the minister of information. Son Sann's party congress in September was

disrupted by two grenade attacks of unknown provenance. The investigation

was brief and unsuccessful.

Funcinpec holds the edge in official power and national government posts,

but the CPP has a much firmer grasp of the local governments across the

country, the bureaucracies, and the military. Ranariddh and Hun Sen each

have portions of the military loyal to them; there are "Hun Sen troops"

and "Ranariddh troops". And when Ranariddh built a large public

park in the capital, using his personal wealth, Hun Sen followed suit with

a park of his own, financed by the wealth he has also somehow amassed.

But in spite of this rivalry, it is difficult to see any ideological differences

among these parties. In fact, I have not detected even the hint of one.

The coalition government has been operating as a partnership in which both

prime ministers cooperate in laying a wide and plush red carpet for all

kinds of foreign investment. As I have mentioned, a substantial portion

of Cambodia's remaining forest has been sold to Malaysian and Indonesian

companies. Two large foreign-owned casinos operate in Phnom Penh, and Singapore's

Raffles hotel chain has bought the two most famous hotels in the country.

The national airline is mostly Malaysian-owned. Slated for privatization

are the state electricity company, the state petroleum company, and the

state insurance company. Hundreds of families west of the capital are soon

to be displaced for Cambodia's first golf course, and Club Med, believe

it or not, is planning to set up a resort in Sihanoukville, where an entire

island has been sold to a Malaysian firm for a casino resort.

They also collaborate in their efforts to protect their partnership by chipping

away at the freedoms which have made a brief appearance in Cambodia since

the elections. They both ardently supported the new press law, with its

vaguely defined proscriptions and strictly defined prison terms, and they

jointly requested, in March, that the United Nations Center for Human Rights

here be closed down.

But with the house arrest of Sirivudh, who has been an ally of Sam Rainsy

and is a prospect for the throne, it appears that Hun Sen has chosen his

moment to assert his power. Ranariddh (who saw in Sirivudh a threat within

his own party) has failed to defend his half-uncle and party leader, who

is one of the few people in Cambodian politics who may have threatened Hun

Sen's rise. Sam Rainsy's party has been outlawed. King Sihanouk may be increasingly

mellow and libera[oops--something went missing here!]ry immunity, without playing the tape, without any defense

by the accused permitted, and without debate. Members leaving the chamber

said that they had no choice. By mid-afternoon, crowds gathered in silence

at both ends of Sirivudh's block on Street 240 as police put him in a car

bound for T3 prison and a very uncertain future. Latest word is that he

has refused an offer to leave the country, preferring to face a trial and

a possible 20-year sentence.

And at the darkest, farthest edge of the Cambodian pond, the Khmer Rouge

still wait, financing themselves with timber sales--just as the government

does--laying mines, shelling a town here and there, and watching the ripples

wash up on the shore.

On Thin Ice: December 8, 1995

Rumored eve of destruction. Dr Gavin Scott is free, but Prince Sirivudh

is still imprisoned--not in the famously decrepit T3 but in a house at the

Ministry of the Interior. He says he will stay and fight the accusation

that he plotted to assassinate Hun Sen, the 2nd Prime Minister. It becaomes

increasingly clear that Prince Ranariddh has everything to gain from the

removal of Sirivudh from their party. As I see it, Ranariddh is providing

a service to Hun Sen, namely, as a government coalition partner he is the

living proof that the government--in reality under the control of Hun Sen--is

really a government of national reconciliation, and thus a worthy recipient

of the international aid that makes up half of Cambodia's income. But now,

perhaps Hun Sen is realizing he does not need Ranariddh, he does not need

foreign aid (and influence, see his speech, below). Maybe he is willing

to have a smaller pie, as long as he gets all of it. There are plenty of

resources here to be sold off.

Meanwhile, Hun Sen has gone down to the "Hun Sen development zone"

in a neighboring province, and, in a speech on Tuesday to the villagers

of Krangyov, called for demonstrations against foreigners and their embassies--in

particular the French and the US embassies, on account of their interference

in Cambodian internal affairs via their aid policies.

The Krangyov villagers are the ones who sacked the office of a newspaper

in Phnom Penh. And it is rumored they are coming to town tomorrow to the

US and French embassies, and the office of the new--and banned--opposition

party of Sam Rainsy. All of which is within spitting distance of guess which

office: The Cambodia Daily. King Sihanouk and Prince Ranariddh have both

left the country for diplomatic trips unrelated to recent events.

On top of it all, our printer has given us two weeks to get our press out

of his shop, claiming that the space is needed by a new tenant. It is tempting

to report a real terror situation here. It's something about the glory of

it all, and getting to be here at an exciting time. Right now it's hard

to tell.

Stop the Presses: December 9, 1995

This morning Hun Sen made a speech to his Krangyov villagers, saying

that The Cambodia Daily is an illegal paper which can be held responsible

if any violence breaks out, such as a grenade explosion at an embassy: "if

there is any blast in the embassy, you will be arrested" ie, for incitement.

There has been a mysterious holdup of our official registration papers,

which seems to be the pretext for calling us illegal. Shortly after this

speech was broad cast on the radio, our printer came by and told us that

he will not print tomorrow's (Mon Dec 11 1995) Cambodia Daily, so we are

looking for a new place to print. Maybe go to a short version on photocopy

if necessary.

Second Prime Minister Hun Sen's Speech of December 9, 1995

This is an unofficial translation of a speech delivered at the disabled

soldiers' center in Kien Svay district, Kandal province. This excerpt is

taken from the latter portion of the speech. Earlier in the speech, Hun

Sen praised disabled war veterans and distributed gifts. Sections especially

about the Daily are in bold.

Relating to the demonstration rumor against foreign embassies

in Phnom Penh, Hun Sen would like to make the statement as follows: I would

like all local and foreign media to record my voice till the end and very

clearly and to broadcast this voice in full length.

In the past few days, I have declared in Sa'ang, Prek Ambel commune, that

seeing that interference from foreign countries in one internal affairs

of Cambodia, against the sovereignty and integrity of Cambodia, is becoming

more and more strong, so that the two PMs cannot tolerate anymore, I have

made an appeal to have a nationalist movement in order to protect the sovereignty

and integrity of this country, ending all interference in this country's

internal affairs.

This movement can be made through the form or aspect of non-violent demonstrations; this movement is only to the level of protecting the sovereignty and independence

of the nation. We have not declared wars against any country, not at all.

What the RG [Royal Government] wants the people to support is only at the

level of protecting the independence and sovereignty of our country, to

stop the interference of foreign countries in the internal affairs of Khmers

and to allow the problems of Cambodia to be solved by its own people. This

intention or aim is the most reasonable wish, according to the national

rights of all sovereign states in this world. This is a vital ritual of

a state with sovereignty and independence and furthermore Cambodia is a

state that has received the guarantee through the Paris agreement signatories,

guaranteeing the sovereignty and independence of Cambodia.

What I want to do, and also the intention of Samdech Krom Preah Ranariddh,

and His Majesty the King's intention, is only to the level of having independence,

sovereignty and territorial integrity. I have clearly said that the people

of Cambodia are prepared to participate in a demonstration to protect the

independence and sovereignty of the country. We have the right to demonstrate.

They have the right to demonstrate, but I do not declare wars yet against

any country and do not also order an attack against the embassy of any country

because if we attack the embassy of any country, it is like making aggression

against that country, as an embassy is a territory with independence and

sovereignty inside our country.

We can make non-violent demonstration by sending protest letters to those

embassies but we cannot enter the embassy. This is the framework that we

want to do, it we are forced to do. Whether the demonstration takes place

or not, depends entirely on the foreign countries, if they stop interfering

in Cambodia or not. If not, the demonstration will take place and take place

all over the country. Because the RG has the right to conduct a demonstration

in order to show that the people of Cambodia support the RG in the protection

of independence and sovereignty of the country and if there is agreement

of RG, I, Hun Sen, would appeal to people to participate in this demonstration.

Because it is a non-violent demonstration and demanding independence, not

to be under foreign intervention in Khmer problems. But I do not order to

attack the embassies, not at all.

Those foreign countries which are not guilty of interfering in Khmer problems,

came to tell me, phoned to certain of my advisors, my ministers and secretaries

of state, saying that what Hun Sen said is correct because this is the problem

of independence and sovereignty. But the foreign countries which are guilty

are very afraid, because they did something nobody knows. Please don't be

afraid or scared; I have said already not to be scared. The only thing is

whether they stop it or not. And another thing not to forget is that nobody

will harm or touch your embassy. Even though, in Paris, the French authorities

have allowed some Khmers of French nationality and some French people to

demonstrate against the Cambodian embassy, but here we do not allow such

things to take place. That is the first thing or problem.

The second problem is there is a rumor that there would be attacks against

the embassies of some countries. I would like the ministry concerned to

see to this matter and if there is violence taking place really in any of

the embassies, investigations must take place immediately into all the newspapers

who publish against the truth.

The tape recording of my speech in Sa'ang Prek Ambel commune, which was

even broadcast on the TV and radio, should be taken to compare whether in

the speech there was something relating to ordering attacks against embassies,

no, there is not such an order. And if there is not such an order by me,

and if any incident happens in any embassy today or in the days ahead,

investigation and surveillance must be conducted against any newspapers

who publish wrongly. From the truth inside that, we include the illegal

newspaper Cambodia Daily. You are not yet fully legal, I heard that you

are not yet legal, if it is not fully legal, why the police allow you to

stay in Cambodia. If it is not legal, we send them back to their own country.

But I do not force the expulsion, we have to do according to the law. Is

there any staff from The Cambodia Daily coming here? You have to be responsible

for your article. I would like to emphasize that if there is any violence

taking place, the one who alters the truth is to be responsible. But first

we have to investigate. I do not frighten those people to escape, do not

run away. No problem, if you are courageous, do not escape or run away.

And please take my statement to broadcast in time for the noon transmission.

All the embassies, do not worry. I do not oppose you. I have been a young

diplomat for 16 years; I know clearly the sovereignty of each country. What

I want to do is on the level of a great movement to protect independence

and sovereignty of the country. And do not consider my country as a small

district of your country. All those embassies do not worry, if I want to

do it I would do it openly. Like last time they said Hun Sen sent tanks

into Phnom Penh, yes it is true I sent 10 tanks on that day (But some said

I sent one tank. Some said I sent three tanks), four tanks from my house

and six tanks from outside. And it is altogether 10 tanks, in case there

was something coming, they would have destroyed it.

I never try to assassinate people secretly. I never think about it. But

if I want to do something I declare in front of a loudspeaker. Like I sent

tanks, I declared that I sent tanks because it is the duty of the RCAF to

protect. I am not hiding anything. If the demonstration starts I would inform

one week in advance. I take one example, I have a good intention to tell

Son Sann to delay his congress and that they should first solve their internal

problem before having it, and Son Sann said he would have his congress as

planned, and when I declared in Kompong Speu province that if Son Sann insisted

to do it then he has to be responsible. And when he held the congress the

bomb exploded really, and they said that it was the action of Hun Sen as

Hun Sen declared before. So the one who declared openly is the one who secretly

threw bombs at the Son Sann house. It is irony. I did not do it. If I do

it I would go in force and do it openly; if there is resistance we would

deal a stronger blow. But it is strange, after declaring openly, that person

secretly throws bombs.

Like now as I openly declared that there would be demonstration, if some

bad guys, 10 to 20 persons, demonstrate and attack their embassy, then I

would be blamed entirely for that. So I would declare to all of you in advance,

the police should look carefully, if I hold a demonstration I would inform

one week in advance. Whether to attend the demonstration or not is the right

of each citizen. But I want just one thing. Any citizen who supports the

government in the protection of independence and sovereignty of the country

to stop the interference of foreign countries, I would like them to stand

along the street for the period of either one hour or 15 minutes or 20 minutes,

all standing in the street, I would do like that so that we do not waste

so much money, and much efforts to march. Just stand on the streets. Then

raise the banners, and send representatives to deliver protest letters to

those embassies or to broadcast on the radio, TV etc.

Then they publish and said that I am organizing demonstrations to attack

embassies instead. So the newspapers who do not publish the truth, should

be prepared. If there is any blast in the embassy, you would be arrested.

We have to arrest without waiting. Because they are the source of the problem;

they turn white to gray, then to black. If you do not want to publish, do

not publish it. If you want to publish you must publish all my statement.

If you publish more or less than the truth, I would use my right, you have

to be careful. That is called creating turmoil. I want to make it clear

we are not making war with any countries; we just want to have the right

to protect our sovereignty. If AFP [Agence France-Presse] come also? And

who are those sharp-nose guys, which agency they are from? They are taking

a lot of pictures, maybe they come for that story also.

Then they publish and said that I am organizing demonstrations to attack

embassies instead. So the newspapers who do not publish the truth, should

be prepared. If there is any blast in the embassy, you would be arrested.

We have to arrest without waiting. Because they are the source of the problem;

they turn white to gray, then to black. If you do not want to publish, do

not publish it. If you want to publish you must publish all my statement.

If you publish more or less than the truth, I would use my right, you have

to be careful. That is called creating turmoil. I want to make it clear

we are not making war with any countries; we just want to have the right

to protect our sovereignty. If AFP [Agence France-Presse] come also? And

who are those sharp-nose guys, which agency they are from? They are taking

a lot of pictures, maybe they come for that story also.

I would like to tell the secret of a foreigner who dare to prepare a draft

statement for an assassination plot witness, for that witness to make a

statement that this assassination plot is a joke, but this witness is quite

smart, he said that I do not know whether he is joking or serious, but he

really said it. Whether it is true or not is the competence of the judge.

I do not understand this foreigner or US citizen who works in the Asia Foundation,

who manipulates the witness statement and this action is in article fifty-

something of the Untac penal code and must be in prison from one to two

years. Now Mr Om Yun Tieng is filing his complaint in the court already

maybe. To pressure the witness is to be in prison, and for foreigner, would

he be in prison or not? The white color, they want to change it to black

or gray. This is our heart's pain or grief. We do not know what was behind

the curtain.

The foreigners who are living in their countries and they did not know anything

about Cambodia, they demand us to free the criminal, but they did not know

anything about that. They recognize that he really said it but as a joke.

Whether it is a joke or not, we should not comment; the judges know their

work. Is it a joke or serious to say that to attack my convoy en route to

Krangyov, using five B-40 rocket launchers?

Like the case of the bomb blast at Son Sann house, if at that time we had

our forces there we would have been able to kill the assailants on the spot,

and we would have had proof of who was doing that thing. [END]

So that should give an impression of the Second Prime Minister. In the few

days since then, there have been no riots or demonstrations yet, we have

found a new printer--for the time being--and come up with contingency plans

in case that falls through. I'm happy to say that we have put out the paper

every day this week. We've removed our printing press from the former print

shop (an Angkorian task in itself which involved moving an outdoor restaurant

that was in the way, cutting through a steel fence, and about ten Daily

staff, print shop workers, and hired contractors rocking it on rollers across

the floor to a forklift that was sinking through the concrete like a hot

penny on butter). On Tuesday Dec 12, King Sihanouk made an offer to Hun

Sen: if he will release and "semi-pardon" Prince Sirivudh, the

King will make sure that Sirivudh goes to France. Hun Sen quickly agreed,

but it is not known yet if Sirivudh will. It would get him out of the country,

which would serve Hun Sen--and his symbiotic partner Prince Ranariddh--quite

well.

That's quite enough for this week. I've been working 12 hours a day and

sleeping the rest. My motorcycle is getting a suspension overhaul, my orange

cat is back, I have two new housemates For my birthday tomorrow, I give

myself a trip to the beach at Sihanoukville--home of white sand so clean

it squeaks, phenomenal seafood, clear cool water and aah.

December 19, 1995

We've been getting clippings from the US press...The New York Times and

the Washington Post, and maybe others, running stories like "Cambodia

slips back into chaos" etc. From here, it looks to be true. The direction

is not positive, rather it seems that the powers here have decided to go

for what they call the "Asian style of democracy" which is their

code word for a sort of corporate autocracy.

January 1, 1996

Politics

Things have calmed down. The power structure has been effectively rearranged,

and those who rearranged it would like to sit back and see what reaction

there will be to their accomplishments. We at the Daily are returning to

our foolhardy ways...until the next time, at least.

Mosquitos

You would think that in the dry season the mosquitos would be on the retreat,

holed up in some moist place, awiting thier opportunity to reproduce once

again in the wet season. No, in fact they are much worse now. They are truly

voracious--they struggle through your hair to bite your scalp, they jam

their proboscis through your socks into your ankles, even through your jeans.

She hovers along your arms as you try to sleep, brushing your skin with

her wings until she finds a the one spot you missed with the DEET. There

she alights, and her hooked feet cling to you as she finds that sweetest

spot where her proboscis can slide gently through to the warm thick blood

within...

Night-time mosquitos hide during the day, like bats. Pick up a dark-colored

item from your laundry pile and a cloud of them disperses confusedly. A

burst of Shelltox at a time like this can lift your mood for the whole day.

Health Care Debate Comes to Cambodia

Anybody who has ever been exposed to my ranting and raving on the farcical

health care debate in the US will understand how dismayed I am that the

health care reform question is rearing its ugly head here. In Cambodia,

there are only a few hundred doctors for a population of around 10 million.

Doctors at public hospitals usually work one or two hours a day and then

leave to work at their private clinic. Nursing staff is in short supply

as well; normally family members of hospitalized patients stay in the hospital

to tend the sick, bring them food, and bribe the staff for attention. Donated

medical equipment is found sitting idle, stripped for parts, or just disappears

without a trace into the black market.

This underfunded system competes with traditional medical methods that include

scraping the skin with the edges of coins until it is raw, and applying

heated glass cups to the forehead, chest or back so that the vacuum inside

the cups breaks capillaries under the skin and leave round red marks. Pharmacies

are also very popular. Feeling under the weather? Buy some random antibiotic

and feed it to yourself intravenously. It's good to get vitamins intravenously

too. Something about having a needle stuck in you really works--it's so

high-tech.

But there is one area in which the Cambodian health system excels, and that

is cash savings. The government here spends just $2.80 per year per person.

Just think of the savings if that could be duplicated in the United States!

What fools we were to fight for a Canadian-style system (let alone the atrocious

Clinton plan) when a Cambodian-style system could have been instituted for

just $700 million a year. Just think about it--a 99.95 percent savings over

the current US system is not too shabby.

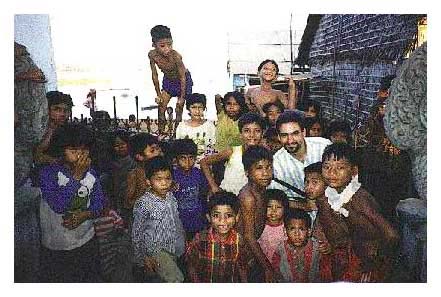

| Me (plaid shirt, front middle) with a bunch of other kids and some foreign guy, at a temple in Kompong Chhnang.

Ha, fooled you. I'm in the striped shirt.

For more about this trip, see Patrice's travelogue.  | |

March 1, 1996

OK, OK, call off the dogs. I'm still here, if harried by computer woes

which have seriously impaired my e-mailability. I have been getting messages-I

don't know if I've gotten all of them-and I've even sent a few, although

it seems clear that those have not all arrived at their destinations.

Selected correspondence:

"HIV" virus hits Cambodia

More than a month ago I received, thanks to Lisa S, the famous e-mail originated

by Young Bradley late last year that attempts to mimic the spread of HIV

by asking people to forward it on. A week later The Cambodia Daily received

and ran a wire story about Young Bradley's experiment. As if that weren't

enough to demonstrate the way these things can spread across the globe,

one week later our network here at the Daily was attacked by a computer

virus that turned our working lives to misery.

Patrice G:

You'll be interested to hear that one of the fast speedboats to Siem Reap

exploded at the dock in Kompong Chhnang--the little town where we got food

poisoning (click for Patrice's account). Remember

that arrangement where they had a 55-gallon drum of gasoline on the back

deck of the boat feeding the engines, and a guy sitting on top of it smoking

cigarettes? No one was seriously injured though.

But last week a small pleasure boat carrying 22 tourists from France capsized and four drowned. It turned

out the boat was being piloted by a 12-year-old and a 7-year-old. So the

government says it will think of some licensing rules for those boats (which

I frequently go out on with friends). It's another example of a chaotic

society gradually introducing the type of regulations we take for granted

in the US, except when we are complaining about them. Another bit of freedom

traded away for security.

Dave the Scot:

I recall we had an elaborate paranoia-fest at Eid restaurant sometime in

August. Recently, I was perusing an old newspaper an ran across this, from

the (Bangkok) Nation, Sept 25,

1995:

NEWCASTLE, England - Robots are potentially capable of threatening

mankind and experts should start looking at ways of curbing their power

now before it is too late, a leading scientist said recently.

"This is the whole of the human race [at risk] if we let it go...It

is possibly a bigger issue than human genetics," Professor Kevin Warwick

said before a keynote speech to a British scientific conference. Warwick

said experiments showed robots could already learn from their own experiences

and from other machines they were linked up to directly. The next stage

is for robots to communicate with others via computer and even on the Internet.

As information was shared, robots could potentially become as "intelligent"

as men, said Warwick, a professor at the University of Reading's cybernetics

department.

Dave H:

Sorry to hear about your Christmas visit from Old Saint Sick. My favorite

part of your account was definitely "slumped on the commode like a

broken puppet." That's quite a popular position here in Cambodia. One

of my housemates may have typhoid right now, and dengue is not so unusual.

But so far the worst I've had was when Patrice and I went to Siem Reap.

I spent a lot more time crawling to that porcelain wat than visiting Angkor

Wat. Full-blown hallucinations, too.

(See Patrice's treatment of this episode)

Christmas in Cambodia? My housemates threw a little party featuring actual

eggnog. They got a little dead bush and hung Buddhas on it, and played Southern

folk songs on the guitar, and also Elvis Presley's Blue Christmas. We went

to work on Christmas Day, a normal workday here in all respects.

Mad about Mad Cow Disease: April 15, 1996

No, there have been no worries about the the dreaded Mad Cow disease here.

Business at the "BurgerMania" fast food restaurant is slow--but

it has been since the place opened a few months ago, and in fact the new

"Lucky Burger" (a dead ringer for Burger King) debuted just a

couple of weeks ago next to Lucky Market.

But despite the lack of Mad Cow panic here in Phnom Penh, some of you may

have noticed references to The Cambodia Daily and its position on Mad Cow

in publications in your part of the world. So follows a great example of

how an idea can spread across the world with next to no effort, if conditions

are exactly right.

One of my workmates, Pip Wood, the national editor, mentioned to me that

our friend Conor had a great idea: Send Britain"s mad cows to Cambodia

to shake and shiver on the minefields here. Ten million cows, ten million

landmines, problem solved.